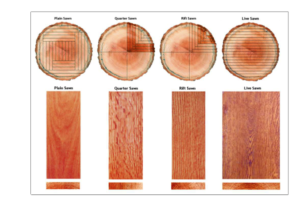

THERE ARE BASICALLY FOUR WAYS YOU CAN MILL A LOG INTO SQUARE-EDGED LUMBER. LET’S TAKE A LOOK AT EACH OF THEM.

THERE ARE BASICALLY FOUR WAYS YOU CAN MILL A LOG INTO SQUARE-EDGED LUMBER. LET’S TAKE A LOOK AT EACH OF THEM.

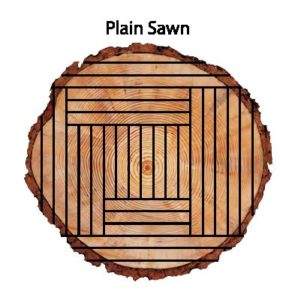

Plain-Sawn (or Flat-Sawn)

Cost effective, abundant

The most efficient and cost-effective way to slice a log into lumber, Plain-Sawing is also the most common lumber you will find. In most boards, you will find cathedral grain patterns, the result of the growth rings running a shallow 30 degrees to the face of the board (“tangential grain”).

Because it’s material- and labor-efficient, Plain-Sawn is also the lowest cost of the cuts. So the advantages are price and interesting appearance. But there’s a downside, too: dimensional instability. That tangential grain is more likely to result in more movement in the wood of in all directions.

There are two ways to minimize this concern. 1. Buy from top-end producers who mill, dry and store their lumber carefully. You can meet two of our partners who fit this description HERE and HERE. 2. Use proper preparation and assembly techniques when building your projects.

In Plain-sawing logs, the sawyer begins slicing boards from one face, then turns the log 90 degrees to yield the next-widest boards. They then continue this sequence to produce the maximum yield from the log. It is efficient and fast and doesn’t waste much wood. Contrast this with the “Live-Sawn” method, below.

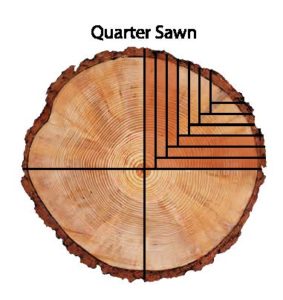

Quarter-Sawn Wood

More Expensive, Shorter Supply

Quarter-sawn lumber boasts very straight grain and, in some species, dramatic and highly prized design element called “flecking”. (Look to mission-style or Arts-and-Crafts, Stickley furniture for examples). This is the result of the grain running a steep 75-to-90 degrees TO the face of the board (“radial grain”): the lines now are spaced very closely together and are comb-like.

In Quarter-Sawing, the sawyer first cuts the log into quarters. Each quarter is then sliced from the inside-out: the widest board is taken first. That quarter is then flipped and the next-widest board is sliced off. Flip again, cut… Watch this, courtesy of our partner, Frank Miller Lumber.

Only the first few center-cut boards meet the definition of quartersawn, with the grain running the requisite 75-90 degrees. They can be wide, but few. The rest of the pieces taken this way will be Rift-sawn (see below).

“Medullary Rays” are cellular structures in wood which radiate out from the center of the tree toward the bark. If you see the end of a freshly-cut log you can see these rays like spokes of a wheel (more easily seen in some species). The steep radial angle of Quarter-Sawing exposes large sections of these cell structures, resulting in the “figure” or “fleck” that creates the desirable design elements mentioned above. These markings are prominent in White and Red Oak. In most other species, Quartered boards look like Rift-sawn.

A very striking example of the results of Quarter-Sawing lumber is “Ribbon” African Mahogany (Khaya). Because of the unique way that this species grows, dramatic wide light/dark stripes of beautiful grain are exposed by quartering the logs. We almost always have Ribbon African in stock.

But there is another huge advantage to Quarter-Sawn lumber: dimensional stability. Quarter-sawn boards are less likely to twist, cup or warp, and we experience less end-checking as well. Quarter-sawn lumber is stronger as well, because the consistent grain structure minimizes internal stresses. So, in addition to its beauty, this reliability and durability is the reason architects and designers find it attractive for flooring, cabinetry, high-and furniture and craftworks.

The downside? Price. Lower yield, labor intensive, fewer mills producing it equals higher cost.

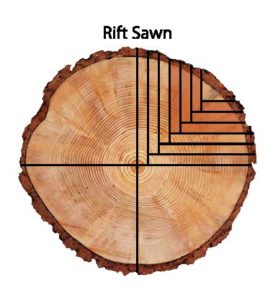

Rift-Sawn

Rift-Sawn

Most expensive, Lowest availability

So, you love the straight-grained appearance of Quarter-Sawn lumber, but the figure and fleck don’t meet your design aesthetic. Solution: Rift-Sawn lumber.

Rift boards can be produced simultaneously within the Quarter-sawing process described above, but they can also be processed separately. The radial grain of Rift-sawn boards runs 30 to 60 degrees (45 degrees is ideal) from the face of the board, resulting in close, straight grain patterns. This shallower cut angle avoids the figure/fleck in Red and White Oak.

Like Quartered lumber, Rift-sawn lumber is more stable in every direction than Plain-Sawn.

Because the Rift boards being cut from the log quarter are closer to the edges, they are narrower than quarter-sawn boards. We will frequently be asked for “wide” rift boards: sorry, that just doesn’t happen (quartered- yes. rift- no). As in Quarter-sawing, there is considerable waste (ex.: four sizeable triangles are left behind from every log after the Quartered and Rift boards are taken away, to be used for other purposes).

So, aside from producing narrower pieces by necessity, Rift-Sawn lumber is going to be more expensive as well.

What’s Trending?

Rift-Sawn Red Oak. Plain-sawn Red Oak was THE hardwood lumber of choice for ages. Check out our lumber yard if you’re looking for some. You’re probably within 50 feet of some plain-sawn red oak right now: that familiar cathedral-grained, honey/amber/gold look. But fashion changes, and that look has given way to different species and different patterns coming into favor: maple, alder, walnut. Lately, though, we’re seeing increasing requests for Rift-sawn Red Oak. Beautiful, durable Oak with a more contemporary straight-grained appearance seems to be a fashion trend with staying power.

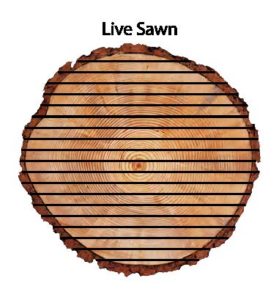

Live-Sawn

Simple, Efficient and Variable Results

Grab a log and start slicing it length-wise. Don’t turn it, just keep cutting ‘til you reach the bottom. Doesn’t get much easier than that.

Live-sawing is how very wide flooring blanks are made, and this is how Live-Edge Slabs are produced (see ours HERE).

What you get in every board is the full gamut of heartwood and sapwood, and grain angles from 90 degrees to almost parallel to the face. In the center the rings will be tight together, nearer the edges they’ll be wide.

When that’s your design aesthetic, Live-sawn lumber can be very beautiful with that mixture of all of the other milling methods apparent in any plank. The cost should be more reasonable that Rift or Quartered lumber.

The downside of Live-Sawn material concerns stability. Particularly in thicker cuts, but prevalent in all boards, is the potential for movement in any direction. It’s hard to counteract all of those stresses working simultaneously against each other. Careful kiln-drying from reliable producers is critical.

Learn about some of our other partners and visit our lumber store today.

THERE ARE BASICALLY FOUR WAYS YOU CAN MILL A LOG INTO SQUARE-EDGED LUMBER. LET’S TAKE A LOOK AT EACH OF THEM.

THERE ARE BASICALLY FOUR WAYS YOU CAN MILL A LOG INTO SQUARE-EDGED LUMBER. LET’S TAKE A LOOK AT EACH OF THEM.

Rift-Sawn

Rift-Sawn